for 4th part HERE

With this in view, we can now interrupt Popier’s lunch so that he can hear the commotion outside in the corridor.

“The Revolution chooses neither its enemies nor their number”, replied the member of the Committee for Public Safety.

“But it can choose how many of them it is going to put to death every day.”

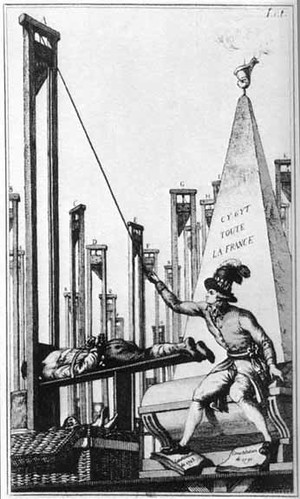

The State Prosecutor explained that according to Sanson, who presumably knew his business, he needed a minimum of two to three minutes for each condemned person at the guillotine and if, as was increasingly the case, there were up to sixty a day, then they claimed more than three hours of his time. Since they seldom arrived at the Place de la Révolution before five o’clock in the afternoon, in winter they would have to work by candlelight, and its counter-revolutionary effect and reactionary symbolism was certainly known to citizen Couthon.

“The guillotine is slow”.

“It can’t be any faster, citizen Couthon”.

“Then the court must be faster, citizen Fouquier-Tinville”.

“Give me a law that will allow it to be so.”

“What the Revolutionary court needs, citizen State Prosecutor, is not a law but revolutionary resolve”.

”That will not make the day any longer”, replied the State Prosecutor. “What will we do with our enemies when winter comes?”

“Nothing”, said Couthon as the second doors opened ahead of him.

“Nothing?”

“Nothing. By winter there won’t be any left.”

The doors closed. Popier lifted his head. History had left the room. Only those who recorded it remained behind, hunched over their thick protocols.

The conversation he overheard was to have fateful consequences not only for enemy citizens of the Republic to whom it referred, but also for citizen Jean-Louis Popier, a loyal employee of the Republic, from which, so far at least, he had kept a respectful distance. Incredible though it may seem, it was the reason why he forgot about his lunch and became a part of history and of our story. For, he assumed that Vilate, the duty member of the Tribunal, would come for the list of the condemned earlier than usual that day and was afraid that if he resumed his lunch, he might not finish entering their names into the records in time.

Trembling, he got down to work. He handed Chaudet the death sentences one by one, as he recorded them, as he hammered in the “nails”, to use the judicial jargon for the “guilt column”, rather than all at once, as he usually did. With a few swift strokes of his goose plume, Chaudet would transform them into the execution list.

Chaudet was just adding the last name to the list when citizen Vilate appeared, earlier and more impatient than usual. Without a word, the judge grabbed the list from him and rushed out of the room. Popier and Chaudet exchanged relieved glances. Chaudet wiped the sweat from his brow. Popier had no need. His body was small and thin and did not perspire, though sometimes he felt that he was made of nothing but water. That he had nothing else inside him.

That night, having returned before the others for his few hours of sleep in the mansard at the Palais de Justice, from where you could see Paris without seeing the Revolution and from where everything had the dark, still, soothing silhouette of indifference, he sat down on the mattress placed on top of the wooden boards, and from his pocket took out the remains of his lunch to eat for dinner. It was wrapped up in a piece of paper that looked familiar. He smoothed out the crumpled sheet, all greasy from the cheese. Leaning toward the candle, he read:

“In the name of the French people…”

It referred to a poor spinner named Germaine Chutier who had declared in the presence of patriotic witnesses that what she missed most in her life was the king. In court she defended herself by claiming that she had said not le roi but le rouet, a spindle. The court took the view that a spinner needed a king more than a spindle and condemned her to death. Today she had been due to pay for her loyalty to the king. But instead of lying under the blade of the guillotine, she was lying on the straw of the Conciergerie, far down below her unwilling savior, citizen Popier, asleep and dreaming of the spindle that would mean more to her life than a king.

He heard the noise in the corridor just in time to slip the paper under his blanket. Scribes Chaudet and Vernet walked into the room. They were back from the Palais Royal. They smelled of drink and girls and were full of talk. Robespierre had delivered a speech at the Convention. He had confined himself to principles and had not mentioned names. Perhaps the Records Room would have a bit of peace and quiet in the coming days. That was Chaudet’s opinion.

“I don’t think so”, said Vernet. Vergnaud spoke too.”

“He spoke well.”

“Too well.”

”What do you think, Popier?”

Popier did not answer. They thought he was asleep.

Asleep in the Conciergerie far down below him was the spinner Germaine Chutier. But Popier was not asleep. Hidden underneath his blanket, he stayed awake all night, tearing up the death sentence and eating it piece by piece.

And so it was that citizen Jean-Louis Popier, scribe of the Revolutionary Tribunal, ate his first death.

He fell asleep just before dawn and dreamed of the guillotine. He had never seen it but he imagined it as a huge iron spindle. Standing next to the black wheel was the hooded executioner. When he climbed up the wooden steps to the platform, Popier saw that it was not Sanson but a woman. She removed her hood and, though he had never seen her before, he recognized Germaine Chutier, the spinner who had favored the spindle over the king. Her face showed neither gratitude nor compassion. She reached out to him with her bony, bloodstained hands, gnarled from spinning the yarn.

Instead of the drum roll that accompanied all executions, he heard from somewhere the melodious sound of a flute. It was playing a cheerful tune, whimsical even, not really appropriate to the scene.

He woke up in a sweat and wet his bed, releasing much of the water he had for so many years retained in a solid state.

On 1 Fructidor, 18 August 1793, he was sitting at his desk, drawing black ink columns in his Protocol for the coming month. He did not think about what he had done the day before. Only thus could he surmount his fear and retain some water inside him. But around noon, when they brought him the day’s death sentences, the very first name, probably because it was again a woman’s, made him think of Germaine Chutier.

The spinner, sitting on the straw strewn over the Conciergerie’s stone floor, was explaining her predicament for the nth time to a handful of the last remaining noblemen. She had not said le roi! She had said le rouet! She needed a spindle not a king! What on earth would she do with a king? She could not make a living with a king. But with a spindle she could. Which was why she expected one from the Revolution. A spindle, not a king! And look what she got! Is this why she had gone hoarse in the galleries of the Convention, shouting for the death of Louis Capet, whom the enemies of the people had wanted to save, they who had not given her a spindle either?

His fear was overcome by a sense of happiness that his own negligence had been the cause of this scene.

No one knows how Popier’s thoughts led him that summer’s day from an act of carelessness that filled him with a mixture of horror and satisfaction, triggering profuse perspiration and the need to pee, to an act of compassion, where horror, fear, satisfaction, his fortunately keen sensory perception and even his giving relief to his bladder all merged into a blur of confusion. He did not keep a diary and none of his oral biographers ever tried to establish whether he had one. They had no need for such bizarre reconstructions because in their eyes Jean-Louis Popier had been an enemy of the Revolution from the start.

The latter versions of the scribe’s life, by which time Homerian imagination had distorted or completely eradicated the few existing reliable facts, describe in detail how, during the September massacre of 1792, he had saved the lives of people first in La Force and then, as the story gained momentum, in other prisons as well – in Châtelet, Salpêtrière and the Conciergerie. There was no unfolding story in these apocrypha, none of the surprises that usually attend acts verging on madness.

All assumptions are, therefore, permissible, as long as they move the story forward.

We can say that when he came across the name of a faceless woman who was due to die that day, the image of Germaine Chutier prompted him to perform a most curious act. It aroused a sense of pity that had been rendered dormant by the marginal and even innocent part he played in the mechanics of the Reign of Terror. Perhaps, too, there was the defiance of someone anonymous and innocent against a fate that made him an accomplice of the guillotine, the co-executor of acts which were decided by others.

We do not know what Popier’s religious beliefs were, or if indeed he had any. Therefore this is not a road that we can pursue, though it would make it easier to understand his actions. Nor can we assume that he read Jean-Jacques Rousseau and thus learned that people are by nature good, incapable of devising the guillotine, and that they were led to invent it because of the bad lives they were forced to live.

All assumptions are indeed permissible, but none suffice to explain how a non-descript little scribe, sitting in his frayed black jacket in the antechamber of the Revolution’s Court of Last Judgment, surrounded by suspicion, distrust, doubt, fear – the inseparable companions of revolutionary vigilance - himself paralyzed with anxiety, dared to chew up the court’s death sentences and arbitrarily revoke the sovereign will of the people, the natural course of revolutionary justice and decisions made by those both more powerful and wiser than he.

This is the picture I am trying to conjure up for the reader.

The August sun makes the Records Room translucent. Everyone is in their shirtsleeves, except for citizen Popier. He is wearing his black jacket, in which he will conceal the purloined death sentence. Alas, he is sweating too much to be able to attribute it to the coat he is wearing in the boiling heat. He keeps running to the toilet. He knew he had water inside him even before, but he never dreamed he had so much of it. Fortunately, even the wiliest of spies of the Public Safety Committee could not distinguish between the sweat of heat and the sweat of fear. (Modern scientific theories about spontaneous reflexes are still not in vogue among the police.)

Everyone is very busy. They can hear the clamoring crowds gathered outside in front of the iron railings of the Palais de Justice, waiting for the cart to carry away the condemned. The hearing is over but muffled voices can still be heard from the courtroom. Judge Le Pelletier rushes out to check something in one of the death sentences lying on Popier’s desk – luckily, this one is still here – and Fouquier-Tinville, the State Prosecutor, pops in, wanting something as well, though Popier is unable to determine exactly what, because just then several loud, perspiring members of the National Guard pass by, and he notices the pale, tense face of Barère from the Committee for Public Safety; and all this is happening at once, in a nightmarish daze, in an unintelligible confusion of blurred images, a chaos of rival emotions, so that he himself does not know how the death sentence of a woman who evoked the image of the spinner Germaine from the depths of the dungeon, as if from the swamp of memory, has found itself crumpled in his hand, and how this hand has found itself inside his coat.

He dared not turn back now. He would never be able to explain to anyone why the death sentence was in such a crumpled condition. But he did not dare shove it into his pocket. Random searches were being carried out. For no apparent reason. Nothing was ever found which did not belong in the Records Room, nor did anything ever go missing which should have been there. The reason for these searches was revolutionary vigilance, and it worked in mysterious ways.

While entering the sentences into the Protocol with his right hand, Popier used his left to tear up the one he stole, stuff the scraps of paper into his mouth and, wetting them down with his tongue, he then swallowed them and reached inside his coat for a fresh morsel.

Thus citizen Jean-Louis Popier, scribe of the Revolutionary Tribunal of the Great French Revolution, ate his second death.

The first of his own volition.

The paper did not taste as bad as the one the night before, the ink did not make him vomit. Both materials now had the sweet taste of his own desire.

for 4th part HERE

No comments:

Post a Comment