Part of the story which has been originally published in “1999” under the title “Novi Jerusalem”, Ljubljana, Zagreb; pp. 118-119, 65-66 © Borislav Pekic; English translation © Bernard Johnson.

for 1st part HERE

The concept of amusement did not exist. If one uses the mutant sense of the word amusement was to be found exclusively in other people. The only amusements were this other people.

Unity with nature had been complete. It is difficult to express this in terms of a world which rejects nature. Whatever one says wouldn’t be enough to describe absolute unity with nature which was achieved in New Jerusalem and in the whole Gulag. It was not only seen in life in close association with animals (rats, moles, wolfs, fleas, laces), but in their general customs.

They slept in the forest, on ice, in water, with nothing to impede the sensation of direct contact with nature and cosmos. That is undoubtedly facilitated by the wearing of summer clothing in areas where the mercury dropped even to 40°C below zero.

(It showed, incidentally, that they had also overcome the climate, not like their primitive world by a technique of isolating themselves from it, but by the regulation of body temperature by pure will-power, otherwise they would have succumbed to the cold long before reaching any kind of perfection.)

Personal possessions had not existed. For a civilization which rejects materialism this is the only natural stand. Those few, always the same, personal objects that had been located alongside the skeletons - a wooden spoon, an empty, battered tin, a needle made out of fish bone - could have had only a ritual significance.

Maybe the greatest innovation of this civilization was togetherness. The rejection of repellent privacy, pernicious individuality and ruinous egocentrism – sacred concepts of the mutant world – was completely rejected. Their program was to live together. They slept, woke up, reposed, lived exclusively together.

The people of New Jerusalem were never alone. (Except maybe with rats, since there were not enough for all in the same moment.) This philosophy i practice made the ZEKs an indivisible spiritual and corporal community - open to all animals, which lived together and reposed together in the grave.

(All graves that I have discovered were collective.) As a proof, however, that no idealism is perfect – which gives it its conviction – there were also people who lived alone in a relative material comfort. They were stationed outside the wire. I have proof that they were rare, or existing convicts who violated the common norms of the society and therefore, probably in order to be rehabilitated were convicted to that strict privacy and materialistic life.

Dogs are my only mystery. According to tradition they were men’s best friends. In the wires of New Jerusalem I didn’t find any dog’s skeletons. All were among the convicts.

(...)

The greatest achievement of this icy proto-civilization was its Para normality. The dream of mankind was incarnated. Whilst a certain lower stratum of life still has to endure the last torments in touch with matter, the upper develops in pure spirituality. The ZEKs’ rudimentary language gave proof of their capacity for paranormal communication.

New Jerusalem’s people spoke little, for they all thought identically, and the thought identically because they all lived identically. (Note: It seems that this supreme ideal satisfies also some historic, the one about brotherhood, liberty, equality.) Speech had always been a means of arriving at a bearable compromise with regard to reality.

As each mutant had his own exclusive reality, speech served as a means of communication with his machines, which maintained that reality. In relation to other people, it was not needed, because they existed for us only theoretically. Our speech disappeared, since there is no other explanation of reality to contradict it.

In New Jerusalem speech had disappeared for the opposite reasons: since everyone’s reality had been the same, there was nothing to be said about it. The reality can only be lived in. ZEKs paranormal powers maybe could be best observed in the effects on nature. Certainly, in order to practice, since there is no other explanation, they moved for miles whole mountains, which an ordinary mortal could not move even an inch, if they pushed it for ages.

The complete absence of art served to confirm without any scientific reservation that in New Jerusalem and in the whole of the Gulag mankind had achieved its archaic goal that life itself should become an artistic category, an artistic skill which would make all others superfluous. On the whole, living there must have been real – art.

The only thing that remained unclear to me was their religious life. I hope nevertheless, that I would be able to understand it as soon as I could decipher one concept which was evidently of a cultural nature. It is the so called “Slop-Drum”, a hollow, cylindrical article which probably expressed the absolute harmony of the community, as well as the harmony of the cosmos, and maybe also the harmony with the cosmos. The universal purpose of it was certain, since it stood in every chamber of New Jerusalem, in the same way as hearth gods and idols protected the homes of the earliest mankind. The secondary proof was the fact that it was not found in any houses of the convict’s colony. It could have meant that the lawbreakers, apart from not being able to participate in communal life, for a time were left without – god.

I had a my disposal an incomplete copy of a book, also found in the northern ice, which was called the ‘Bible’ and was, apparently, the history of some earlier imperfect world which had abounded in clear violence and unclear philosophy. In it were mentioned large number of divinities but the Slop-Drum was not amongst them. I had, however, found New Jerusalem. Of it was written:

“And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and showed me that great city, the Holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God. Having the glory of God, and her light was like unto a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal ...”

I, mutant Arno, as a result of this discovery, had been happy and sad. Happy that the prophecy had been fulfilled, sad that it had lasted for such a short time. (...)

The mystery of “sending to the cellar for fourteen days”, had been resolved, he had found a way out of the syllogism which had seemed to be a dead end.

If some generally accepted right – either to happiness of justice, for example – was not realized, it did not have to mean that it was deliberately denied. That would be something quite natural in an imperfect community. In an ideal one, it would have contradicted its ideal nature. As New Jerusalem had undoubtedly been a model for a perfect society, the crown of the best tendencies of the materialistic proto-civilization, the failure to realize some general right could have come about only because objective conditions for it had not existed.

(His expert judgment was that in the bad proto-state there had been hunger, because food had been badly distributed; in the good one, because there had been none. For the people involved, this perhaps had not made a significant difference, since they died in the same way both from the absence of food and because of injustice in its division, but for historical science, it was crucial.)

It was quite simply that a right which was generally accepted, could not be satisfied, because the conditions were not right for it. In this instance, the rats were a limiting condition of happiness because there were not enough of them. From this point onwards, his conclusion flowed in a quite routine way.

It followed logically, that given a scarcity of rats, happiness could be realized only in shifts. It had to shared, even though by the nature and understanding of the ZEK-civilization it was indivisible. It could only be enjoyed from time to time. And only for a limited time.

This kind of happiness of course, because there was evidence that people deprived of the enjoyment of the cellar and the rats, in the meantime, while they were awaiting their turn with the rats, were kept happy in other ways. (...)

A profound feeling for justice, implying that nothing living should be deprived of happiness had been appended to the general principles of the wise civilization of New Jerusalem.

From what he had found out about the past, it was certain that the crucial problem for first Mankind, a problem which in all probability had destroyed it, had been in arriving at an accord between the general right to happiness and the general right to justice. In the eternal ice of the North, these two rights had finally been associated, the contradiction of existence had been resolved, the eternal ideal achieved, the circle finally closed:

in New Jerusalem everyone had the right to his moment with the rats.

for 1st part HERE

Tuesday, October 31, 2006

Sunday, October 29, 2006

New Jerusalem (4th part)

Part of the story which has been originally published in “1999” under the title “Novi Jerusalem”, Ljubljana, Zagreb; pp. 63-65; 117-118, © Borislav Pekic; English translation © Bernard Johnson.

for 5th part HERE

And so far, they had not been able to resist him nor disrupt him from carrying out any of his actions however much wrong it was.

They could express their displeasure only by trying to persuade him, (and here he was immune, here he was protected by his own truth, the rat in man’s embrace), or by the inefficient execution of archaeological tasks, not formulated in unambiguous orders, something that, because of his absent-mindedness, he was sometimes prone to.

They could express their displeasure only by trying to persuade him, (and here he was immune, here he was protected by his own truth, the rat in man’s embrace), or by the inefficient execution of archaeological tasks, not formulated in unambiguous orders, something that, because of his absent-mindedness, he was sometimes prone to.

Before he had become aware of such dirty tricks, fifty years had passed, during which time his scientific results because of such obstruction had been poor. Now he got round them by not only concentrating on the content but also on the form of the commands which he gave in connection with excavations or the technique of conservation.

It no longer happened that undoubtedly with treacherous premeditation, and not by unfortunate accidents as he had supposed, that one of extremely rare written proofs of the superiority of the frozen New Jerusalem’s civilization over the mutants’ was destroyed simply because he had been imprecise in his instructions regarding the method of the document’s restoration,

Luckily, one document, evidently a form of regulation or proclamation had not been totally spoilt. The robots strove for perfection, but they were not yet perfect. Otherwise there would not have been any documents left. As it was, there remained the final part of a sentence which was important, may be even crucial, for the correct interpretation of the “frozen” way of thought.

From it the concept of life in New Jerusalem stood out with hologrammatic vividness and clarity.

He had spent several years on the translation of the preserved sentence into his own language, after being confronted with numerous semantic difficulties, quite unavoidable when trying to explain the concept of one language by the concepts of a completely opposite, which above all one could not understand, since in the present world nothing corresponds neither in reality nor in memory.

But it had been worth it. Transcribed, the fragment of the sentence said:

TO BE SENT TO THE CELLAR FOR FOURTEEN DAYS.

If he had not already dug up the wonderful skeleton, if he had not known what was in the cellar, even if it had been successfully translated, the sentence would have remained unclear.

“Sending into the cellar” without rats would have had no sense. In the cellar fortunately were rats.

Moles too. And there had also been found a frozen nests of lice and fleas, charming little creatures; the first calm and inactive, the second of a more lively and mischievous habits, plebeian temperament, which, it seemed, the members of the ZEK species - that was how the New Jerusalem people had called themselves - bred as domestic pets and companions and even kept on their own bodies, going nowhere without them.)

The combined skeletons of man, rat and mole, with the aforementioned nests of noble sub-cultures, depicted for him unambiguously as actual eye-witnesses the system of mutual relationships desirable in the New Jerusalem civilization and perhaps the summit of an ideal condition.

He was however conscious of the fact that as a scientist he always had to be careful and not rush ahead with premature conclusions.

For it was not out of the question that in the still uninvestigated regions of the planet, somewhere in the south, west or east, might be a preserved still more advanced New Jerusalem, a still more perfect form of human happiness as a result of friendship with rats, fleas and moles.

In any case “sending into the cellar amongst the rats” could not be evaluated, if he wanted to remain a scientist, according to the present understanding about them (which as part of an obscure nature is rejected) outside the context of already established criteria for happiness in that community.

In that way it could have only two logical meanings:

that to be sent into the cellar was especially good for whoever was sent there, but, for unknown reasons, it could be enjoyed for only a limited period of time, in this particular instance – fourteen days. (Later he found proofs that the community with rats could last even for years.)

The explanation, although logically irreproachable, did not satisfy him. There was something unnatural in it. It was as if the good that came out of it were - a privilege. A definite priority which was not given to all and which had to be merited in some way, in some special way, to which, evidently, had been dedicated the first, now lost part of the sentence.

The New Jerusalem man had been sent to the cellar as a reward, and not because, even though for a short term, the pleasure in the exclusive company of rats was his natural right. And that, once again logically, contradicted the proven ideal nature of New Jerusalem.

A community where the good was not general, innate, an unalienable right, but which could be attained by and depended on human actions, which could, but did not have to be enjoyed, was not ideal, although it could be orientated towards perfection if there were continually more and more individuals in possession of that good, (brotherhood with rats), and less and less of those who were deprived of it.

But the New Jerusalem community, the world of Gulag in general, as the inhabitants of this archipelago have been called – pointing probably to that meaning of the term that people of the proto-language attributed to the word “heaven” and “Eden” – had been ideal. All his other primary and secondary archeological finds had indicated that. In it life was good (the life with rats) only generally and given to all equally by naturalization of citizenship, the same as has been in the primitive society of that period where you acquire the right to take part in electing a bad government.

(...)

Their material culture had been almost non-existent. Obviously a residue of barbarism. Its rudimentary forms (dilapidated wooden huts, uncomfortable ramshackle beds, chairs which nowadays would be used only for torture), had been kept, it seemed, only to remind the people of New Jerusalem of the senseless burden from which they had been released when their aspirations had been directed towards more virtuous and pure spirituality. Sometime also as a symbol. (The barbed wire – a symbol of inseparable community.)

Their food had been puritan. There had been clear efforts on the whole community to eat as little as possible. Supposition of a high probability: in an attempt for the conditions of metabolism to be entirely transferred to paranormal forces and for man to be finally fried from his physical nature.

That of course had been an ideal which was difficult, if not impossible to realize. But nevertheless, he had evidence to show that many of the ZEKs abstained from food for days on end in order to quicken that elate state.

(...)

Work in that world is one of the great contributions to humanity. In the mutant world it was carried out by cybernet, and always had some purpose. In New Jerusalem, work had no meaning, and no purpose, except for its own sake, and hence it arrived at that profoundest hidden sense which all civilizations, both before and after New Jerusalem’s had sought for in vain.

The sense of work was therefore exclusively in the work itself and nothing else. Temporary and periodical benefits were no more than its chance by-product. I am not sure, I have not enough facts, if those sporadic gains are covering some real needs of that, in all other aspects satisfied, community – and that in itself would be self-contradictory –

or whether it was the usual error and the technical omissions in the corresponding activity. When they were building a house, which was sometimes even finished, was this the result of some remnant need or a sad failure.

(Commentary: It was simply incredible that the wisdom of all those successive human civilizations, like a blind man next to a full bowl, had overlooked the simple, almost simplistic and obvious conclusion that work could only have a sense if it realized it within itself, and it could realize it within itself only if it was senseless.)

for 5th part HERE

for 5th part HERE

And so far, they had not been able to resist him nor disrupt him from carrying out any of his actions however much wrong it was.

They could express their displeasure only by trying to persuade him, (and here he was immune, here he was protected by his own truth, the rat in man’s embrace), or by the inefficient execution of archaeological tasks, not formulated in unambiguous orders, something that, because of his absent-mindedness, he was sometimes prone to.

They could express their displeasure only by trying to persuade him, (and here he was immune, here he was protected by his own truth, the rat in man’s embrace), or by the inefficient execution of archaeological tasks, not formulated in unambiguous orders, something that, because of his absent-mindedness, he was sometimes prone to.Before he had become aware of such dirty tricks, fifty years had passed, during which time his scientific results because of such obstruction had been poor. Now he got round them by not only concentrating on the content but also on the form of the commands which he gave in connection with excavations or the technique of conservation.

It no longer happened that undoubtedly with treacherous premeditation, and not by unfortunate accidents as he had supposed, that one of extremely rare written proofs of the superiority of the frozen New Jerusalem’s civilization over the mutants’ was destroyed simply because he had been imprecise in his instructions regarding the method of the document’s restoration,

Luckily, one document, evidently a form of regulation or proclamation had not been totally spoilt. The robots strove for perfection, but they were not yet perfect. Otherwise there would not have been any documents left. As it was, there remained the final part of a sentence which was important, may be even crucial, for the correct interpretation of the “frozen” way of thought.

From it the concept of life in New Jerusalem stood out with hologrammatic vividness and clarity.

He had spent several years on the translation of the preserved sentence into his own language, after being confronted with numerous semantic difficulties, quite unavoidable when trying to explain the concept of one language by the concepts of a completely opposite, which above all one could not understand, since in the present world nothing corresponds neither in reality nor in memory.

But it had been worth it. Transcribed, the fragment of the sentence said:

TO BE SENT TO THE CELLAR FOR FOURTEEN DAYS.

If he had not already dug up the wonderful skeleton, if he had not known what was in the cellar, even if it had been successfully translated, the sentence would have remained unclear.

“Sending into the cellar” without rats would have had no sense. In the cellar fortunately were rats.

Moles too. And there had also been found a frozen nests of lice and fleas, charming little creatures; the first calm and inactive, the second of a more lively and mischievous habits, plebeian temperament, which, it seemed, the members of the ZEK species - that was how the New Jerusalem people had called themselves - bred as domestic pets and companions and even kept on their own bodies, going nowhere without them.)

The combined skeletons of man, rat and mole, with the aforementioned nests of noble sub-cultures, depicted for him unambiguously as actual eye-witnesses the system of mutual relationships desirable in the New Jerusalem civilization and perhaps the summit of an ideal condition.

He was however conscious of the fact that as a scientist he always had to be careful and not rush ahead with premature conclusions.

For it was not out of the question that in the still uninvestigated regions of the planet, somewhere in the south, west or east, might be a preserved still more advanced New Jerusalem, a still more perfect form of human happiness as a result of friendship with rats, fleas and moles.

In any case “sending into the cellar amongst the rats” could not be evaluated, if he wanted to remain a scientist, according to the present understanding about them (which as part of an obscure nature is rejected) outside the context of already established criteria for happiness in that community.

In that way it could have only two logical meanings:

that to be sent into the cellar was especially good for whoever was sent there, but, for unknown reasons, it could be enjoyed for only a limited period of time, in this particular instance – fourteen days. (Later he found proofs that the community with rats could last even for years.)

The explanation, although logically irreproachable, did not satisfy him. There was something unnatural in it. It was as if the good that came out of it were - a privilege. A definite priority which was not given to all and which had to be merited in some way, in some special way, to which, evidently, had been dedicated the first, now lost part of the sentence.

The New Jerusalem man had been sent to the cellar as a reward, and not because, even though for a short term, the pleasure in the exclusive company of rats was his natural right. And that, once again logically, contradicted the proven ideal nature of New Jerusalem.

A community where the good was not general, innate, an unalienable right, but which could be attained by and depended on human actions, which could, but did not have to be enjoyed, was not ideal, although it could be orientated towards perfection if there were continually more and more individuals in possession of that good, (brotherhood with rats), and less and less of those who were deprived of it.

But the New Jerusalem community, the world of Gulag in general, as the inhabitants of this archipelago have been called – pointing probably to that meaning of the term that people of the proto-language attributed to the word “heaven” and “Eden” – had been ideal. All his other primary and secondary archeological finds had indicated that. In it life was good (the life with rats) only generally and given to all equally by naturalization of citizenship, the same as has been in the primitive society of that period where you acquire the right to take part in electing a bad government.

(...)

Their material culture had been almost non-existent. Obviously a residue of barbarism. Its rudimentary forms (dilapidated wooden huts, uncomfortable ramshackle beds, chairs which nowadays would be used only for torture), had been kept, it seemed, only to remind the people of New Jerusalem of the senseless burden from which they had been released when their aspirations had been directed towards more virtuous and pure spirituality. Sometime also as a symbol. (The barbed wire – a symbol of inseparable community.)

Their food had been puritan. There had been clear efforts on the whole community to eat as little as possible. Supposition of a high probability: in an attempt for the conditions of metabolism to be entirely transferred to paranormal forces and for man to be finally fried from his physical nature.

That of course had been an ideal which was difficult, if not impossible to realize. But nevertheless, he had evidence to show that many of the ZEKs abstained from food for days on end in order to quicken that elate state.

(...)

Work in that world is one of the great contributions to humanity. In the mutant world it was carried out by cybernet, and always had some purpose. In New Jerusalem, work had no meaning, and no purpose, except for its own sake, and hence it arrived at that profoundest hidden sense which all civilizations, both before and after New Jerusalem’s had sought for in vain.

The sense of work was therefore exclusively in the work itself and nothing else. Temporary and periodical benefits were no more than its chance by-product. I am not sure, I have not enough facts, if those sporadic gains are covering some real needs of that, in all other aspects satisfied, community – and that in itself would be self-contradictory –

or whether it was the usual error and the technical omissions in the corresponding activity. When they were building a house, which was sometimes even finished, was this the result of some remnant need or a sad failure.

(Commentary: It was simply incredible that the wisdom of all those successive human civilizations, like a blind man next to a full bowl, had overlooked the simple, almost simplistic and obvious conclusion that work could only have a sense if it realized it within itself, and it could realize it within itself only if it was senseless.)

for 5th part HERE

New Jerusalem (3rd part)

Part of the story which has been originally published in “1999” under the title “Novi Jerusalem”, Ljubljana, Zagreb; pp. 61-63 © Borislav Pekic; English translation © Bernard Johnson.

for 4th part HERE

All of nature, while it had still existed, had been like that. Both the ugliest, as was the better part of it, and that which, adapted to man’s imagination, could be looked at differently, without arousing disgust, possessed that insolent, arrogant self-confidence of the self-created.

Everything that was right, good, artificial, depended on something outside itself, could be classified according to external criteria which always defined the value of the thing created in relation to something else of the same species, or according to its purpose, if no model for it existed and could in every respect be subjected to comparison.

A stream could not be compared with a hill or a waterfall with a forest thicket. From the analogy between sea and lake nothing could be derived apart from the conclusion that both were full of lifeless hydrogen and oxygen in the proportion of two to one.

There was no point in saying which of two stones was better, even if that were possible. The grass was absolutely, almost insanely useless in every of its shape, and the primeval forest useless in a completely different way from each individual tree.

The stars turned senselessly, empty spheres, indifferent to the Earth, which, for its part, knew nothing of them until wise robots discovered their sense for the creation of that Earth, the metal womb of its Species. Nature depended only on itself; its products had no standards, patterns nor rules which guaranteed artificial creations their purposefulness, harmony and beauty.

Nature was ruled by Father Cronus (Chance) and Mother Gaea (Chaos), the cause and result of despair in the human world, and the basis in it of the merciless indifference of events.

But what could the New Jerusalem’s proto-man have found in that indifference, what had bound him to nature, joined him to it enough to erase all the differences between men and rats – according to his hypothesis, the basis of human history – so that he, Arno, should have extracted the skeletons of that history out of the hollow of a carbonized tree, from underground areas, which, when they had been functioning, must have been submerged in water at least up to knee height, this was the sole remaining enigma in the otherwise logically irrefutable interpretation of New Jerusalem, which he had recently also solved.

A little later, he was standing on the top of a bare hillock from which the worn stone crumbling away a mark of some fossil, probably of an ancient horse.

Shading his eyes with his hand from the reflection of the setting sun on the metal shoulder of the robot sent out to reconnoiter. The time until its return – he was hoping for news that the other man had bee found – he intended to spend with the meadow.

He expected the unpleasantness of escort by the machines, programmed with enmity towards nature as a hostile principle of creation, from which man was excepted because he was no longer born but modeled in placenta simulators with the hope that, in the distant future, he would be free of the last spark of repulsive mortal life and take on the immortal perfection and sterile purity of a cybernet.

He had long ago got used to their quiet resistance, the resistance of the obedient. It had been going on for almost two hundred and fifty years, if the criss-cross pattern of his primitive calendar were to be believed, in which it was, on the only place on the planet, where time had been re-established.

The fact that he alone of all the mutants worked, even bothered to occupy himself with something - although with the robots at his side nobody really needed him - was quite enough to arouse suspicions. The fact that his work was to do with archaeology, a proto-science inseparably linked with the phenomenon of time, made things even worse.

Given the current knowledge of the past of the Species - without the revolutionary correction to be found in his discovery - and the awareness that that past must have been what it had been, (although in fact it was not known what it had been), that it must have ended in cataclysm, for otherwise it would not have been what it had been, (if it in fact had been),

to take an interest in it in any of its aspects, particularly in the archaeological one, where it must have been at its most disastrous, causal, primordial, creative, could in that history-less time only mean a serious processing confusion in the mutation of the genetic material from which he, Arno, had been produced.

And if there had still been a government, authorities, law, or any kind of compulsion, even only surviving customs, if each man had not by now been entirely independent, his own mankind, hermetically isolated from every other individual-mankind, this out-of-the-ordinariness would have meant serious personal repercussions for him.

At the very least, an operation to remove the error from his brain. But to arrive at that monstrous conclusion regarding the imperfection, and even the failure of the mutant way of life from that unnatural work, and deduce the superiority of that of the proto-people, if one looked at it though the undoubtedly highest model, New Jerusalem frozen into northern ice, was quite beyond the computation power of his robots.

The desire for this monstrous error to be revealed as the truth - as the need unfelt for thousands of years to actually communicate something, even though it itself was monstrous - went well beyond the measure of built-in tolerance of even the most primitive machines in his service, those pitiful screws whose intelligence knew only of the routes of their own corresponding printed circuits.

But they could do nothing about it. They were prevented by the three-part law A.S.I.M.O.V., built-in to every cybernetic creation as an everlasting principle as far back as the dawn of the Simulation Era:

in all circumstances even as far as self-destruction, the robots had to obey him and defend him, except in the case of him raising his head against another man, (and since it was not known where other men were, this was hardly likely), or, against himself; if he had demanded that they help him to commit suicide, or not to hinder him from doing so.

He sensed that in these exceptional circumstances too the robots might find a possibility of opposing his eccentricities.

If they were to interpret an attack on the mutant idea of solitude, incorporated into the central nucleus of the mutant way of survival as “raising his hand against himself”, if the attempt to do away with the present civilization through the discovery of its senselessness could be seen as suicide – for by doing away with it he would also be doing away with himself, then they could justify their action on two counts:

the prevention of murder and the prevention of suicide, and arrive at the annulment of the A.S.I.M.O.V. prohibition and do something about it. In either case, his iron mentors would have cause for reflection.

But the case was without precedent. To arrive at such ideas would require them to put into operation lengthy and complicated reflective combinations. He hoped that his proclamation of the truth would precede their conclusion that they were allowed to prevent him by force.

for 4th part HERE

for 4th part HERE

All of nature, while it had still existed, had been like that. Both the ugliest, as was the better part of it, and that which, adapted to man’s imagination, could be looked at differently, without arousing disgust, possessed that insolent, arrogant self-confidence of the self-created.

Everything that was right, good, artificial, depended on something outside itself, could be classified according to external criteria which always defined the value of the thing created in relation to something else of the same species, or according to its purpose, if no model for it existed and could in every respect be subjected to comparison.

A stream could not be compared with a hill or a waterfall with a forest thicket. From the analogy between sea and lake nothing could be derived apart from the conclusion that both were full of lifeless hydrogen and oxygen in the proportion of two to one.

There was no point in saying which of two stones was better, even if that were possible. The grass was absolutely, almost insanely useless in every of its shape, and the primeval forest useless in a completely different way from each individual tree.

The stars turned senselessly, empty spheres, indifferent to the Earth, which, for its part, knew nothing of them until wise robots discovered their sense for the creation of that Earth, the metal womb of its Species. Nature depended only on itself; its products had no standards, patterns nor rules which guaranteed artificial creations their purposefulness, harmony and beauty.

Nature was ruled by Father Cronus (Chance) and Mother Gaea (Chaos), the cause and result of despair in the human world, and the basis in it of the merciless indifference of events.

But what could the New Jerusalem’s proto-man have found in that indifference, what had bound him to nature, joined him to it enough to erase all the differences between men and rats – according to his hypothesis, the basis of human history – so that he, Arno, should have extracted the skeletons of that history out of the hollow of a carbonized tree, from underground areas, which, when they had been functioning, must have been submerged in water at least up to knee height, this was the sole remaining enigma in the otherwise logically irrefutable interpretation of New Jerusalem, which he had recently also solved.

A little later, he was standing on the top of a bare hillock from which the worn stone crumbling away a mark of some fossil, probably of an ancient horse.

Shading his eyes with his hand from the reflection of the setting sun on the metal shoulder of the robot sent out to reconnoiter. The time until its return – he was hoping for news that the other man had bee found – he intended to spend with the meadow.

He expected the unpleasantness of escort by the machines, programmed with enmity towards nature as a hostile principle of creation, from which man was excepted because he was no longer born but modeled in placenta simulators with the hope that, in the distant future, he would be free of the last spark of repulsive mortal life and take on the immortal perfection and sterile purity of a cybernet.

He had long ago got used to their quiet resistance, the resistance of the obedient. It had been going on for almost two hundred and fifty years, if the criss-cross pattern of his primitive calendar were to be believed, in which it was, on the only place on the planet, where time had been re-established.

The fact that he alone of all the mutants worked, even bothered to occupy himself with something - although with the robots at his side nobody really needed him - was quite enough to arouse suspicions. The fact that his work was to do with archaeology, a proto-science inseparably linked with the phenomenon of time, made things even worse.

Given the current knowledge of the past of the Species - without the revolutionary correction to be found in his discovery - and the awareness that that past must have been what it had been, (although in fact it was not known what it had been), that it must have ended in cataclysm, for otherwise it would not have been what it had been, (if it in fact had been),

to take an interest in it in any of its aspects, particularly in the archaeological one, where it must have been at its most disastrous, causal, primordial, creative, could in that history-less time only mean a serious processing confusion in the mutation of the genetic material from which he, Arno, had been produced.

And if there had still been a government, authorities, law, or any kind of compulsion, even only surviving customs, if each man had not by now been entirely independent, his own mankind, hermetically isolated from every other individual-mankind, this out-of-the-ordinariness would have meant serious personal repercussions for him.

At the very least, an operation to remove the error from his brain. But to arrive at that monstrous conclusion regarding the imperfection, and even the failure of the mutant way of life from that unnatural work, and deduce the superiority of that of the proto-people, if one looked at it though the undoubtedly highest model, New Jerusalem frozen into northern ice, was quite beyond the computation power of his robots.

The desire for this monstrous error to be revealed as the truth - as the need unfelt for thousands of years to actually communicate something, even though it itself was monstrous - went well beyond the measure of built-in tolerance of even the most primitive machines in his service, those pitiful screws whose intelligence knew only of the routes of their own corresponding printed circuits.

But they could do nothing about it. They were prevented by the three-part law A.S.I.M.O.V., built-in to every cybernetic creation as an everlasting principle as far back as the dawn of the Simulation Era:

in all circumstances even as far as self-destruction, the robots had to obey him and defend him, except in the case of him raising his head against another man, (and since it was not known where other men were, this was hardly likely), or, against himself; if he had demanded that they help him to commit suicide, or not to hinder him from doing so.

He sensed that in these exceptional circumstances too the robots might find a possibility of opposing his eccentricities.

If they were to interpret an attack on the mutant idea of solitude, incorporated into the central nucleus of the mutant way of survival as “raising his hand against himself”, if the attempt to do away with the present civilization through the discovery of its senselessness could be seen as suicide – for by doing away with it he would also be doing away with himself, then they could justify their action on two counts:

the prevention of murder and the prevention of suicide, and arrive at the annulment of the A.S.I.M.O.V. prohibition and do something about it. In either case, his iron mentors would have cause for reflection.

But the case was without precedent. To arrive at such ideas would require them to put into operation lengthy and complicated reflective combinations. He hoped that his proclamation of the truth would precede their conclusion that they were allowed to prevent him by force.

for 4th part HERE

Saturday, October 28, 2006

New Jerusalem (2nd part)

Part of the story which has been originally published in “1999” under the title “Novi Jerusalem”, Ljubljana, Zagreb; pp.58-61 © Borislav Pekic; English translation © Bernard Johnson.

for 3rd part HERE

(...)

As soon as he disembarked from the helicar with a chosen cybernetic escort he saw at once to his satisfaction that there was nothing on the island that contradicted the possibility of human life there. As everywhere else on the planet, nature had been fundamentally, methodically eradicated.

Any micro-fauna that had temporarily avoided annihilation had retreated into the ground, leaving on the surface only the least noticeable and most resistant insects: chameleons, masters of mimicry, and fleas, those bed-fellows of eternity. The rare flora had returned to the forms of their mossy origins, or recalled their dim, logogrammatic images but only as carbonized, friable skeletons.

The ground had taken on the ghostly color of washed-out lime and rocks crumbled to dust at the slightest breath of wind. In cracks and hollows a trickle of water, slowly choking without oxygen, and the dry beds of ancient rivers sent up eddies of purple dust like startled phantoms. Nothing here could have prevented man from developing and perfecting his precious solitude.

Nothing, except one still living patch of earth, discovered near the camp the day after they had landed. Although it was only a limited area, something that in more barbarous times must have been a pasture or some such useless vestige of land, and stretched out only as far as the stunted edge of a line of half withered elm trees behind which there dragged itself, thick and heavy as pitch, the all-but defunct current of a primeval stream; nature here lived as if there were no man, or as if he did not concern it.

But he was deterred from getting back into the helical and flying off at once by the evidence that life here was scarcely noticeable, in fact it was disappearing. And in addition, it was reduced to a meadow dug up by molehills, incapable of infecting the majestic deadness of the surrounding programmed zone with the life of which it itself had less than sufficient.

His robots neither shared his opinion nor felt that the meadow was quite so innocent of danger.

They were well aware that the regenerative power of nature was barely less than their own – although it was nonsensical, since it didn’t produce anything useful - and that a single bud on some by chance neglected tree, if left enough of time, was enough to once again set up the deadly cycle,

to again produce the prehistorical slime, from it to create one-cell organisms, aging to colonize it into poly-organic structures, then to form them again into amphibians and led them onto the solid ground, start a regime of sheer chaos on the planet, and return man to the slavery of its unpredictability.

They had wanted to pacify the meadow immediately with the standard combination of mechanical bulldozing and the injection of a lethal dose of radioactivity, but he would not allow it. (...)

The robots had a built-in, codified memory of the Species, the history of its mutations, induced as spontaneous (although, apart from his, another case spontaneity he didn’t know), the origins of the way of life they had adopted, the explanation of the collapse of the First Mankind –

The robots had a built-in, codified memory of the Species, the history of its mutations, induced as spontaneous (although, apart from his, another case spontaneity he didn’t know), the origins of the way of life they had adopted, the explanation of the collapse of the First Mankind –

he doubted that it was very different from that passed down through inherited human tradition – perhaps even something which was of significant concern for the New Jerusalem proto-civilization, whose super-human warmth must have been preserved even by the ice, and which called the description of that collapse into question.

For that, one simply needed the right key. That was what he lacked. None of the mutant had it. It was as if that key, after memory had been filled and closed off, had been thrown away into nature to disappear with it. And before he found it, deep within himself, like some missing part, or in nature itself, perhaps even in that miserable patch of meadow whose existence, as if to spite everything else, had some purpose, message, secret, he would not be able to rid himself of it. Nor of the robots, however much he couldn’t stand them, for the key, since it could be in them.

Like all mutants, he paid little head to nature. There was nothing personal in that, it was just that his experience of it, apart in the form of the ever-changing ice, a kind of solidified illusion, had been almost nil.

But he was a chimera, in the language of the proto-people – a procedural’s error in the laboratory recombination of his parents’ genes, an unforeseen retrogressive mutant in the strictly progressive mutation process of the Species, some unclear and inexplicable reversion in the continual forward progress of Second Mankind towards the perfection of individual self-sufficiency.

He was the firs scientist in the course of eons of people’s reconditioning against useful work and reflective thought – which was left to machines, programmed never to allow again a situation where the human hand, mind, will, any kind of human capability’s individual participation would ever be needed again – and from all other mutants, each more distant from each other and each more perfect in his different way, he too was different – but in an unheard of and dangerous respect:

he had been born with a flair, quite unknown to his contemporaries, for finding certain likenesses even in the greatest differences, and with a longing to bring them closer together, and that in an era of ideal separation, with other separate identities in order to re-establish a unified World from the deliberately dispersed particles of what had once been a Whole, a World once again capable of remembering and prepared to be continued, a World which would not permit of any Third Mankind and in whose innate lasting continuation nothing would begin again from the beginning.

The discovery that nature was part of a deep, if inexplicable, relationship with the people of the frozen New Jerusalem civilization - a community of man, rat and mole, was his incomplete but approximate model – led him to suppress his genetic revulsion towards everything not created by a robotic pseudo hand, invented by its pseudo mind, everything not artificial, and to overcome the principle that “life is a copy of a machine that works badly and man is an image of an imperfect robot”, and directed him towards a study of nature whenever he had the opportunity to come across it in any shape or size at all.

It happened, in fact, very rarely, but it did happen. It had happened now, when suddenly, instead of the expected grayness of a dead landscape, he had caught sight of the love field over which dandelions flaunted their yellow flowers.

It gleamed in the golden sunlight with golden glow, quite unaware of its striking ugliness. Like a deranged cripple, a veteran of a score of lost battles, and proud of his truncated stumps.

for 3rd part HERE

for 3rd part HERE

(...)

As soon as he disembarked from the helicar with a chosen cybernetic escort he saw at once to his satisfaction that there was nothing on the island that contradicted the possibility of human life there. As everywhere else on the planet, nature had been fundamentally, methodically eradicated.

Any micro-fauna that had temporarily avoided annihilation had retreated into the ground, leaving on the surface only the least noticeable and most resistant insects: chameleons, masters of mimicry, and fleas, those bed-fellows of eternity. The rare flora had returned to the forms of their mossy origins, or recalled their dim, logogrammatic images but only as carbonized, friable skeletons.

The ground had taken on the ghostly color of washed-out lime and rocks crumbled to dust at the slightest breath of wind. In cracks and hollows a trickle of water, slowly choking without oxygen, and the dry beds of ancient rivers sent up eddies of purple dust like startled phantoms. Nothing here could have prevented man from developing and perfecting his precious solitude.

Nothing, except one still living patch of earth, discovered near the camp the day after they had landed. Although it was only a limited area, something that in more barbarous times must have been a pasture or some such useless vestige of land, and stretched out only as far as the stunted edge of a line of half withered elm trees behind which there dragged itself, thick and heavy as pitch, the all-but defunct current of a primeval stream; nature here lived as if there were no man, or as if he did not concern it.

But he was deterred from getting back into the helical and flying off at once by the evidence that life here was scarcely noticeable, in fact it was disappearing. And in addition, it was reduced to a meadow dug up by molehills, incapable of infecting the majestic deadness of the surrounding programmed zone with the life of which it itself had less than sufficient.

His robots neither shared his opinion nor felt that the meadow was quite so innocent of danger.

They were well aware that the regenerative power of nature was barely less than their own – although it was nonsensical, since it didn’t produce anything useful - and that a single bud on some by chance neglected tree, if left enough of time, was enough to once again set up the deadly cycle,

to again produce the prehistorical slime, from it to create one-cell organisms, aging to colonize it into poly-organic structures, then to form them again into amphibians and led them onto the solid ground, start a regime of sheer chaos on the planet, and return man to the slavery of its unpredictability.

They had wanted to pacify the meadow immediately with the standard combination of mechanical bulldozing and the injection of a lethal dose of radioactivity, but he would not allow it. (...)

The robots had a built-in, codified memory of the Species, the history of its mutations, induced as spontaneous (although, apart from his, another case spontaneity he didn’t know), the origins of the way of life they had adopted, the explanation of the collapse of the First Mankind –

The robots had a built-in, codified memory of the Species, the history of its mutations, induced as spontaneous (although, apart from his, another case spontaneity he didn’t know), the origins of the way of life they had adopted, the explanation of the collapse of the First Mankind –he doubted that it was very different from that passed down through inherited human tradition – perhaps even something which was of significant concern for the New Jerusalem proto-civilization, whose super-human warmth must have been preserved even by the ice, and which called the description of that collapse into question.

For that, one simply needed the right key. That was what he lacked. None of the mutant had it. It was as if that key, after memory had been filled and closed off, had been thrown away into nature to disappear with it. And before he found it, deep within himself, like some missing part, or in nature itself, perhaps even in that miserable patch of meadow whose existence, as if to spite everything else, had some purpose, message, secret, he would not be able to rid himself of it. Nor of the robots, however much he couldn’t stand them, for the key, since it could be in them.

Like all mutants, he paid little head to nature. There was nothing personal in that, it was just that his experience of it, apart in the form of the ever-changing ice, a kind of solidified illusion, had been almost nil.

But he was a chimera, in the language of the proto-people – a procedural’s error in the laboratory recombination of his parents’ genes, an unforeseen retrogressive mutant in the strictly progressive mutation process of the Species, some unclear and inexplicable reversion in the continual forward progress of Second Mankind towards the perfection of individual self-sufficiency.

He was the firs scientist in the course of eons of people’s reconditioning against useful work and reflective thought – which was left to machines, programmed never to allow again a situation where the human hand, mind, will, any kind of human capability’s individual participation would ever be needed again – and from all other mutants, each more distant from each other and each more perfect in his different way, he too was different – but in an unheard of and dangerous respect:

he had been born with a flair, quite unknown to his contemporaries, for finding certain likenesses even in the greatest differences, and with a longing to bring them closer together, and that in an era of ideal separation, with other separate identities in order to re-establish a unified World from the deliberately dispersed particles of what had once been a Whole, a World once again capable of remembering and prepared to be continued, a World which would not permit of any Third Mankind and in whose innate lasting continuation nothing would begin again from the beginning.

The discovery that nature was part of a deep, if inexplicable, relationship with the people of the frozen New Jerusalem civilization - a community of man, rat and mole, was his incomplete but approximate model – led him to suppress his genetic revulsion towards everything not created by a robotic pseudo hand, invented by its pseudo mind, everything not artificial, and to overcome the principle that “life is a copy of a machine that works badly and man is an image of an imperfect robot”, and directed him towards a study of nature whenever he had the opportunity to come across it in any shape or size at all.

It happened, in fact, very rarely, but it did happen. It had happened now, when suddenly, instead of the expected grayness of a dead landscape, he had caught sight of the love field over which dandelions flaunted their yellow flowers.

It gleamed in the golden sunlight with golden glow, quite unaware of its striking ugliness. Like a deranged cripple, a veteran of a score of lost battles, and proud of his truncated stumps.

for 3rd part HERE

Friday, October 27, 2006

New Jerusalem (1st part)

Part of the story which has been originally published in the book “1999” under the title “Novi Jerusalem”, Ljubljana, Zagreb; pp.53-57 © Borislav Pekic; English translation © Bernard Johnson.

for 2nd part HERE

Dedicated to Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

1st part

“Decades pass, the scars and wounds of the past

heal over for ever. During that time, some

of the islands of the Archipelago have fallen

apart and been covered by the polar sea of

oblivion. But one day in the future, the

Archipelago, its air, the bones of its

dwellers, frozen into the northern ice, will

be discovered by our descendants like some

incredible salamanders ...”

(A. Solzhenitsyn, “The Gulag Archipelago”)

“And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and showed me that great city, the Holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God. Having the glory of God, and her light was like unto a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal ...”

(Revelation 21-10)

It was the rat’s skeleton which had opened his eyes to it all.

It would have meant nothing, of course, if it had been found by itself in the ice-bound cave of the New Jerusalem settlement where the proto-man’s underground shelter had been preserved, frozen solid, or together with the remains of other rats.

But it had been dug up in close proximity with the skeleton of a man and a mole, and it was that that has given the archeological find its enormous importance, equivalent to the discovery of Troy in the history of First Mankind.

The skeletons were clasped tightly round each other – as in some bony cradle, the animals deep in the man’s pelvis zone – and all three had been caught in the hibernating grip of northern ice crystals for millions of years, most probably from 1999 and the world cataclysm of which they had been part.

For exactly how long could not really be known since the calculation of time had long since ceased.

for 2nd part HERE

Dedicated to Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

1st part

“Decades pass, the scars and wounds of the past

heal over for ever. During that time, some

of the islands of the Archipelago have fallen

apart and been covered by the polar sea of

oblivion. But one day in the future, the

Archipelago, its air, the bones of its

dwellers, frozen into the northern ice, will

be discovered by our descendants like some

incredible salamanders ...”

(A. Solzhenitsyn, “The Gulag Archipelago”)

“And he carried me away in the spirit to a great and high mountain, and showed me that great city, the Holy Jerusalem, descending out of heaven from God. Having the glory of God, and her light was like unto a stone most precious, even like a jasper stone, clear as crystal ...”

(Revelation 21-10)

It was the rat’s skeleton which had opened his eyes to it all.

It would have meant nothing, of course, if it had been found by itself in the ice-bound cave of the New Jerusalem settlement where the proto-man’s underground shelter had been preserved, frozen solid, or together with the remains of other rats.

But it had been dug up in close proximity with the skeleton of a man and a mole, and it was that that has given the archeological find its enormous importance, equivalent to the discovery of Troy in the history of First Mankind.

The skeletons were clasped tightly round each other – as in some bony cradle, the animals deep in the man’s pelvis zone – and all three had been caught in the hibernating grip of northern ice crystals for millions of years, most probably from 1999 and the world cataclysm of which they had been part.

For exactly how long could not really be known since the calculation of time had long since ceased.

Thursday, October 26, 2006

The writer in exile

This fragment has been originally published in “Pisma iz tudjine”, “Znanje”, Zagreb; pp. 13-16. © Borislav Pekic; English translation ©Zdenka Krizman and Maja Samojlov, as “Letters from London”.

You may wonder – not without reason – what a Yugoslav writer is doing in London. Why isn’t he in his own country, where – by the very nature of his calling – a writer ought to be? Why isn’t he with his own people, immersed in the reality of his land, in the environs of the language in which he writes?

Why isn’t he living among the people he is writing for?

At first glance, this is an unnatural state of affairs. But, if we look back in time, we will see that history is full of such “unnatural” situations. It is almost unnatural for a writer to live at home. The great figures of the future of Russian literature, from Solzhenitsyn to Zinovyev, are writing in the West.

At first glance, this is an unnatural state of affairs. But, if we look back in time, we will see that history is full of such “unnatural” situations. It is almost unnatural for a writer to live at home. The great figures of the future of Russian literature, from Solzhenitsyn to Zinovyev, are writing in the West.

Ionesco, Milosz, Kundera, Kochout, and Szkvoretzky are here. Marguerite Yourcenar lives in the United States, Robert Graves on a Spanish island. The English poet Auden is dying in Switzerland and the Columbian Marquez gained fame in Paris for the Hispano-American literature.

Between the two World Wars, the “lost generation” of Anglo-American writers moved to Europe, into voluntary exile from the way of life they had renounced so that, paradoxically, they might portray it more profoundly and deeper, from the farthest possible physical distance and from the most exclusive spiritual independence.

You may wonder – not without reason – what a Yugoslav writer is doing in London. Why isn’t he in his own country, where – by the very nature of his calling – a writer ought to be? Why isn’t he with his own people, immersed in the reality of his land, in the environs of the language in which he writes?

Why isn’t he living among the people he is writing for?

At first glance, this is an unnatural state of affairs. But, if we look back in time, we will see that history is full of such “unnatural” situations. It is almost unnatural for a writer to live at home. The great figures of the future of Russian literature, from Solzhenitsyn to Zinovyev, are writing in the West.

At first glance, this is an unnatural state of affairs. But, if we look back in time, we will see that history is full of such “unnatural” situations. It is almost unnatural for a writer to live at home. The great figures of the future of Russian literature, from Solzhenitsyn to Zinovyev, are writing in the West.Ionesco, Milosz, Kundera, Kochout, and Szkvoretzky are here. Marguerite Yourcenar lives in the United States, Robert Graves on a Spanish island. The English poet Auden is dying in Switzerland and the Columbian Marquez gained fame in Paris for the Hispano-American literature.

Between the two World Wars, the “lost generation” of Anglo-American writers moved to Europe, into voluntary exile from the way of life they had renounced so that, paradoxically, they might portray it more profoundly and deeper, from the farthest possible physical distance and from the most exclusive spiritual independence.

Wednesday, October 25, 2006

Where are Yugoslavia’s billionaires?

This fragment has been originally published in “Pisma iz tudjine”, “Znanje”, Zagreb; pp. 89-92. © Borislav Pekic; English translation ©Zdenka Krizman and Maja Samojlov, as “Letters from London”.

One knows in principle who and where the British billionaires are and one could only be mistaken in the number of billions. In any case you are not going to find them in the same place as ours. Where you are going to find ours I will try to explain. For that I have to turn to one of my visits to the fatherland.

There was a dose of vengeance in my desire to observe the English entering my country. For, in my time, I have had to enter England in the face of polite, but considerable, difficulty. Over and over again, I have had to explain my presence in Britain. The question was not unusual. I had been asking myself the same thing all along.

There was a dose of vengeance in my desire to observe the English entering my country. For, in my time, I have had to enter England in the face of polite, but considerable, difficulty. Over and over again, I have had to explain my presence in Britain. The question was not unusual. I had been asking myself the same thing all along.

Aboard the plane bound for the Adriatic with a large group of Britons and a few Yugoslavs, I said to myself: your time has come. However, the British breezed through passport control, while I was once more called upon to do some explaining. One thing they wanted to know was why I specifically wanted to visit the coast in August. Luckily, the smooth passage of the British was just a trick, and later they had to pay for it.

The line at the Passport Control moved quickly. Then a cold air hostess appeared with a group of my agitated countrymen, leading them ahead to jump the queue in order to catch a connecting flight to Belgrade which was waiting for them. This we all understood. What we failed to understand was why they were still at the airport when we were already well on our way to the coast.

One knows in principle who and where the British billionaires are and one could only be mistaken in the number of billions. In any case you are not going to find them in the same place as ours. Where you are going to find ours I will try to explain. For that I have to turn to one of my visits to the fatherland.

There was a dose of vengeance in my desire to observe the English entering my country. For, in my time, I have had to enter England in the face of polite, but considerable, difficulty. Over and over again, I have had to explain my presence in Britain. The question was not unusual. I had been asking myself the same thing all along.

There was a dose of vengeance in my desire to observe the English entering my country. For, in my time, I have had to enter England in the face of polite, but considerable, difficulty. Over and over again, I have had to explain my presence in Britain. The question was not unusual. I had been asking myself the same thing all along.Aboard the plane bound for the Adriatic with a large group of Britons and a few Yugoslavs, I said to myself: your time has come. However, the British breezed through passport control, while I was once more called upon to do some explaining. One thing they wanted to know was why I specifically wanted to visit the coast in August. Luckily, the smooth passage of the British was just a trick, and later they had to pay for it.

The line at the Passport Control moved quickly. Then a cold air hostess appeared with a group of my agitated countrymen, leading them ahead to jump the queue in order to catch a connecting flight to Belgrade which was waiting for them. This we all understood. What we failed to understand was why they were still at the airport when we were already well on our way to the coast.

Tuesday, October 24, 2006

Ne-vreme u naslonjači

Publikovano u Odabrana dela Borislava Pekića, knjiga 12, Tamo gde loze plaču, (str. 404-405). - Beograd, Partizanska knjiga, 1984, © Borislav Pekić.

Sedim u fotelji pored baštenskog prozora. Iza stakla natiče moluskno-žuto more. Poput diareje. Priroda je dobila proliv i sve je kaki-žuto. Žutilo prodire u nameštaj koji pucketa svuda oko mene. Zujanje obližnje drvare, kao panika desorijentisanog tvrdokrilca, udara o staklo sluha ...

S radija Rossini, uvertira „Sémiramis“. Tajfun zvuka. Zatim Strauss „Imperijalni valcer“. Zamah još traje. A onda antiklimaks – Adagio, Albinoni, pogreb u kasnu jesen, apsolutno beznađe, kraj ...

S radija Rossini, uvertira „Sémiramis“. Tajfun zvuka. Zatim Strauss „Imperijalni valcer“. Zamah još traje. A onda antiklimaks – Adagio, Albinoni, pogreb u kasnu jesen, apsolutno beznađe, kraj ...

Na zidu, preko puta, hlad postaje tvrd. Promene se stalno događaju. Samo treba imati vremena i oko. Parket je uglačan voskom. Prijatan miris izobilja. Izobilja nema, samo njegov miris u vosku. Pravom i onom iz memorije ...

Smrkava se. Fekalične boje prirode postaju crne. Sve tamni kao na slikama starih majstora. Samo jedan zlatan zrak, kao koplje zaboravljeno na bojištu. Takvo koplje, ali olovno sivo, nosi i riter, kome na zidnom goblenu višeglava aždaja nudi svoj, bledim pamukom, izvežen trbuh ...

Kakva je to noć koja mi dolazi kao lopov?

Noć slobode koja nam je izrečena kao presuda na smrt?

Noć zavere protivu pravca vlastitog krvotoka?

Noć ustanka senki koje će nam se otkinuti s peta da na naličju ovog sveta stvore svoj?

Noć u kojoj će me, između dva noža, nadživeti samo stid?

Noć prostitucije sa uzalodnostima?

Smaknuća koje se ne oseća?

Noć posle koje se savest nalazi tamo gde smo ostavili papuče?

Noć u kojoj se trune na rukama uspomena?

Noć Leonida Njegovana, koji će, ako bude stvoren, pucati ne da se brani, nego da diže buku, u nadi da će je neka budućnost čuti?

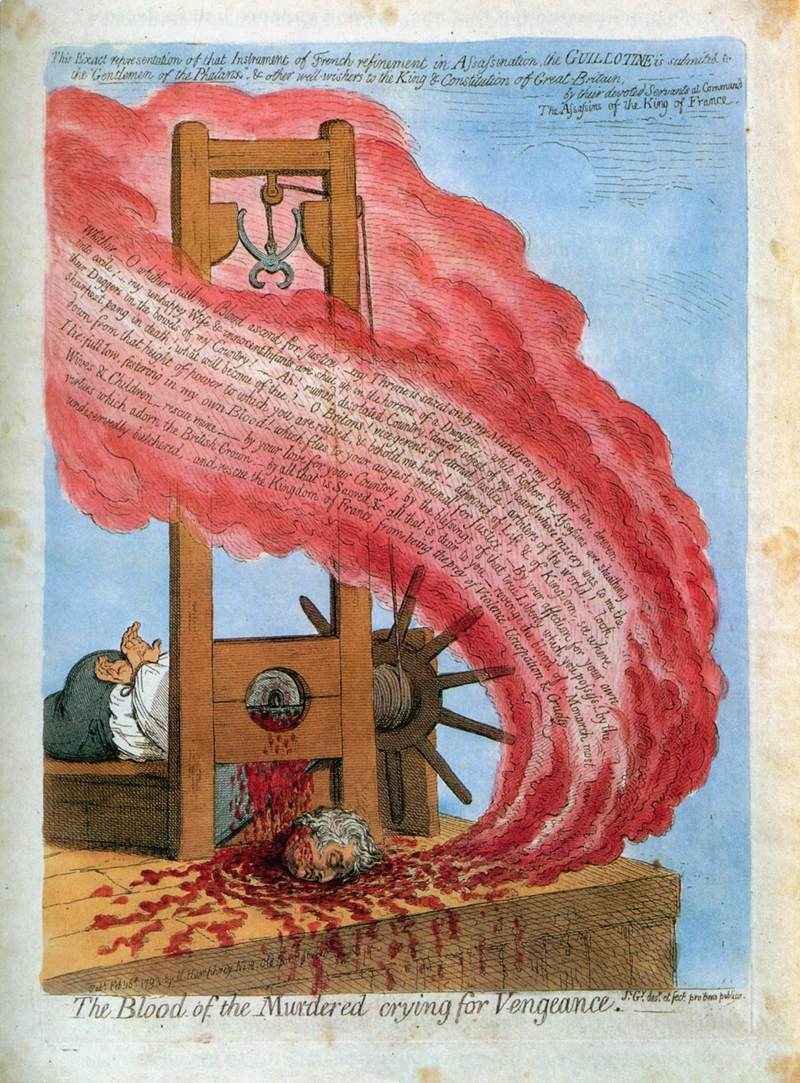

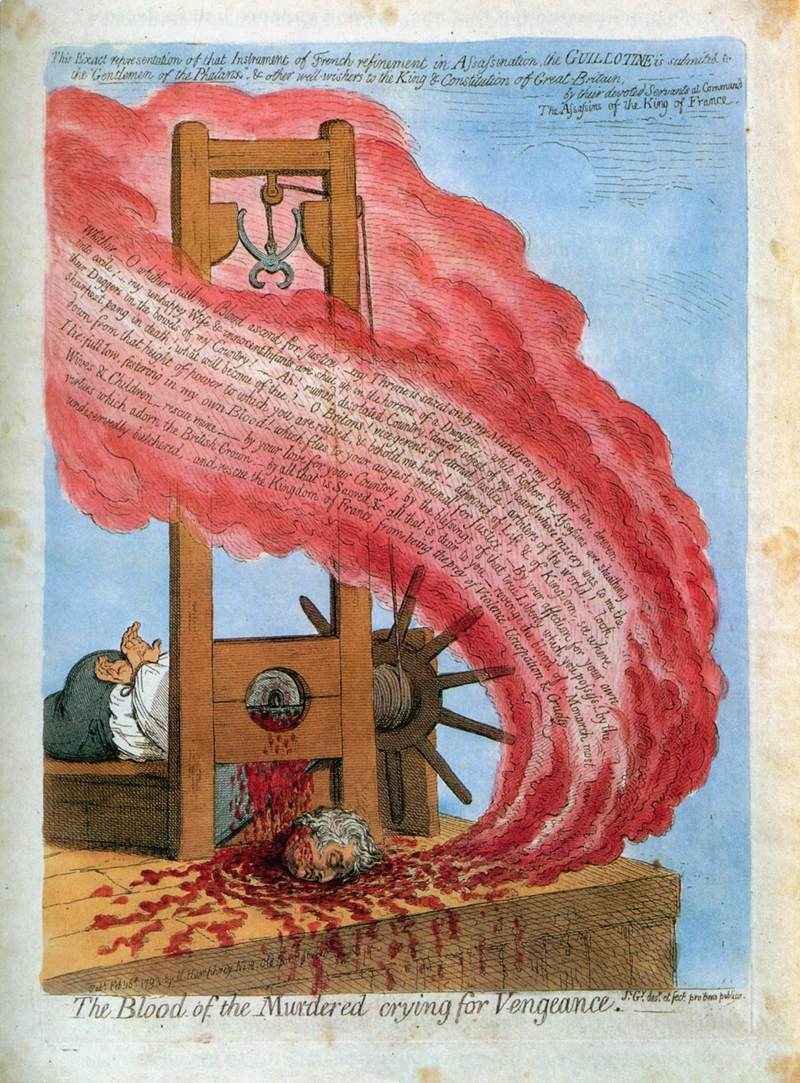

Noć La Gen-a, koji je čekajući zoru i giljotinu, učio pravopis?

Noć straženja pred Onim što će doći, a ja neću znati ni dan ni čas u koji će doći? ...

Osam je sati. Vreme je da se spremim za doček Nove godine. Sutra je 1955. Pa šta?...

Sedim u fotelji pored baštenskog prozora. Iza stakla natiče moluskno-žuto more. Poput diareje. Priroda je dobila proliv i sve je kaki-žuto. Žutilo prodire u nameštaj koji pucketa svuda oko mene. Zujanje obližnje drvare, kao panika desorijentisanog tvrdokrilca, udara o staklo sluha ...

S radija Rossini, uvertira „Sémiramis“. Tajfun zvuka. Zatim Strauss „Imperijalni valcer“. Zamah još traje. A onda antiklimaks – Adagio, Albinoni, pogreb u kasnu jesen, apsolutno beznađe, kraj ...

S radija Rossini, uvertira „Sémiramis“. Tajfun zvuka. Zatim Strauss „Imperijalni valcer“. Zamah još traje. A onda antiklimaks – Adagio, Albinoni, pogreb u kasnu jesen, apsolutno beznađe, kraj ...Na zidu, preko puta, hlad postaje tvrd. Promene se stalno događaju. Samo treba imati vremena i oko. Parket je uglačan voskom. Prijatan miris izobilja. Izobilja nema, samo njegov miris u vosku. Pravom i onom iz memorije ...

Smrkava se. Fekalične boje prirode postaju crne. Sve tamni kao na slikama starih majstora. Samo jedan zlatan zrak, kao koplje zaboravljeno na bojištu. Takvo koplje, ali olovno sivo, nosi i riter, kome na zidnom goblenu višeglava aždaja nudi svoj, bledim pamukom, izvežen trbuh ...

Kakva je to noć koja mi dolazi kao lopov?

Noć slobode koja nam je izrečena kao presuda na smrt?

Noć zavere protivu pravca vlastitog krvotoka?

Noć ustanka senki koje će nam se otkinuti s peta da na naličju ovog sveta stvore svoj?

Noć u kojoj će me, između dva noža, nadživeti samo stid?

Noć prostitucije sa uzalodnostima?

Smaknuća koje se ne oseća?

Noć posle koje se savest nalazi tamo gde smo ostavili papuče?

Noć u kojoj se trune na rukama uspomena?

Noć Leonida Njegovana, koji će, ako bude stvoren, pucati ne da se brani, nego da diže buku, u nadi da će je neka budućnost čuti?

Noć La Gen-a, koji je čekajući zoru i giljotinu, učio pravopis?

Noć straženja pred Onim što će doći, a ja neću znati ni dan ni čas u koji će doći? ...

Osam je sati. Vreme je da se spremim za doček Nove godine. Sutra je 1955. Pa šta?...

Monday, October 23, 2006

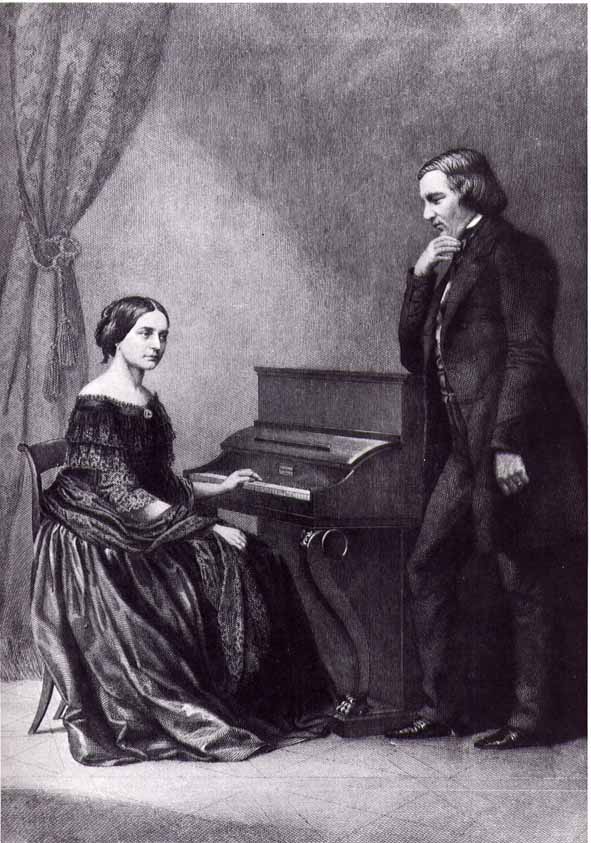

Crni građanski redengot

Publikovano u Odabrana dela Borislava Pekića, knjiga 12, Tamo gde loze plaču, (str. 402-404). - Beograd, Partizanska knjiga, 1984, © Borislav Pekić.

Crni građanski redengot i crveni prsluk Théophile Gautier-a

Jedna od najsvirepijih posledica velikih poraza je migracija forme. Pobednik stvarno pobeđuje tel naknadno, kad vam počne uzimati ono zašta ste se borili, kad od vaše forme započne praviti svoju prirodu ...

Revolucionarne pobede odnose se nad onim društvenim snagam, kod kojih je nekadašnja priroda, iscrpevši vitalnost postala tek – forma. Preuzeta od pobednika, postaje postepeno ona opet priroda, ali njegova ...

Istovremeno se događa suprotan proces. Poraženi prihvataju formu pobednika, koja postaje njihova priroda.

Procesu revitalizacije na jednoj strani proporcionalno odgovara proces devitalizacije na drugoj. Pobeđeni se regeneriše, pobednik degeneriše.

Istorijski primeri ...

Postoji i naš.

Odbacili smo svaki odgoj i pravili od sebe budale da bismo srušili režim. Prihvatili smo od levice davno napušteni promiskuitet, i namesto građanskih dogmi opijali se egzistancijalističkim nihilizmom i rakijom (pri čemu nas je rakija više i brže opijala). Oblačili smo se kao strašila da bismo sablaznili komunističke puritance koji su demonstrirali građansku strogost i jednostavnost ...

Odbacili smo svaki odgoj i pravili od sebe budale da bismo srušili režim. Prihvatili smo od levice davno napušteni promiskuitet, i namesto građanskih dogmi opijali se egzistancijalističkim nihilizmom i rakijom (pri čemu nas je rakija više i brže opijala). Oblačili smo se kao strašila da bismo sablaznili komunističke puritance koji su demonstrirali građansku strogost i jednostavnost ...

Migriraju uvek najpre preteranosti ...

Revolucija postaje patron porodice i cvrčka na ognjištu, koga simbolizuje nezgrapno temeljan nameštaj firme „Todor Dukin“, a građanska klasa, u licu svojih naslednika (bez nasleđa), predaje se zavereničkim organizacijama po kućama, čiji su prozori zamračeni kao u vreme bombardovanja.

Revolucija pledira za Red i Rad; građanska klasa, koja je i Red i Rad pronašla, premda se poslednjim i nije uvek lično bavila, propoveda Nered i Nerad, a zatim odlazi u kafane da ih, praveći buku, simulira.(Pevanje „Uskliknimo s ljubavlju“ na pravoslavnu Novu godinu.)

Revolucija preuzima nacionalne mitose, mladi ih šoveni izlažu preziru. (Jer „Uskliknimo ...“ je buka, nije ideja.) Revolucija dreždi za kancelarijskim stolovima, izmišljajući zakone koji će joj obezbediti trajnost; pasionirani obožavatelji zakona i trajnosti, građani, kuju planove kako da ih izigraju, kako promenu stalnom da učine.

Revolucija je sela u naslonjač; oni koji su naslonjač smatrali jedinom prednošću koja nas razlikuje od životinje, odaju se histeričnoj pokretljivosti, i zamaranju bez svrhe. Revolucija je najzad počela da razlikuje ljude u bezobličnoj „narodnoj masi“, koju joj je u nasleđe ostavila ideologija; građanstvo žrtvuje svoje individualnosti kolektivnim zaverama, karbonarskom mraku u kome sve mačke moraju biti crne i sve jednako presti.

Revolucija čita starog Balzac-a, gleda „Labudovo jezero“, sluša Mozart-a i skuplja se u red pred izložbama klasičnih majstora. Mi pretpostavljamo Schönberg-a, Joyce-a, Picasso-a, pa su nam već i oni pomalo staromodni. Revolucija igra tango iz Burskog rata, mi držimo da je Rock prespor ...

Kao Théophile Gautier na premijeri Hugo-Verdi-jevih „Hernani“-a, građanska klasa oblači crveni prsluk da sablazni revoluciju, koja po istorijskim foajeima već uveliko hoda u salonroku sa kamelijom u zapučku ...

Crni građanski redengot i crveni prsluk Théophile Gautier-a

Jedna od najsvirepijih posledica velikih poraza je migracija forme. Pobednik stvarno pobeđuje tel naknadno, kad vam počne uzimati ono zašta ste se borili, kad od vaše forme započne praviti svoju prirodu ...

Revolucionarne pobede odnose se nad onim društvenim snagam, kod kojih je nekadašnja priroda, iscrpevši vitalnost postala tek – forma. Preuzeta od pobednika, postaje postepeno ona opet priroda, ali njegova ...

Istovremeno se događa suprotan proces. Poraženi prihvataju formu pobednika, koja postaje njihova priroda.

Procesu revitalizacije na jednoj strani proporcionalno odgovara proces devitalizacije na drugoj. Pobeđeni se regeneriše, pobednik degeneriše.

Istorijski primeri ...

Postoji i naš.

Odbacili smo svaki odgoj i pravili od sebe budale da bismo srušili režim. Prihvatili smo od levice davno napušteni promiskuitet, i namesto građanskih dogmi opijali se egzistancijalističkim nihilizmom i rakijom (pri čemu nas je rakija više i brže opijala). Oblačili smo se kao strašila da bismo sablaznili komunističke puritance koji su demonstrirali građansku strogost i jednostavnost ...

Odbacili smo svaki odgoj i pravili od sebe budale da bismo srušili režim. Prihvatili smo od levice davno napušteni promiskuitet, i namesto građanskih dogmi opijali se egzistancijalističkim nihilizmom i rakijom (pri čemu nas je rakija više i brže opijala). Oblačili smo se kao strašila da bismo sablaznili komunističke puritance koji su demonstrirali građansku strogost i jednostavnost ...Migriraju uvek najpre preteranosti ...

Revolucija postaje patron porodice i cvrčka na ognjištu, koga simbolizuje nezgrapno temeljan nameštaj firme „Todor Dukin“, a građanska klasa, u licu svojih naslednika (bez nasleđa), predaje se zavereničkim organizacijama po kućama, čiji su prozori zamračeni kao u vreme bombardovanja.

Revolucija pledira za Red i Rad; građanska klasa, koja je i Red i Rad pronašla, premda se poslednjim i nije uvek lično bavila, propoveda Nered i Nerad, a zatim odlazi u kafane da ih, praveći buku, simulira.(Pevanje „Uskliknimo s ljubavlju“ na pravoslavnu Novu godinu.)

Revolucija preuzima nacionalne mitose, mladi ih šoveni izlažu preziru. (Jer „Uskliknimo ...“ je buka, nije ideja.) Revolucija dreždi za kancelarijskim stolovima, izmišljajući zakone koji će joj obezbediti trajnost; pasionirani obožavatelji zakona i trajnosti, građani, kuju planove kako da ih izigraju, kako promenu stalnom da učine.

Revolucija je sela u naslonjač; oni koji su naslonjač smatrali jedinom prednošću koja nas razlikuje od životinje, odaju se histeričnoj pokretljivosti, i zamaranju bez svrhe. Revolucija je najzad počela da razlikuje ljude u bezobličnoj „narodnoj masi“, koju joj je u nasleđe ostavila ideologija; građanstvo žrtvuje svoje individualnosti kolektivnim zaverama, karbonarskom mraku u kome sve mačke moraju biti crne i sve jednako presti.

Revolucija čita starog Balzac-a, gleda „Labudovo jezero“, sluša Mozart-a i skuplja se u red pred izložbama klasičnih majstora. Mi pretpostavljamo Schönberg-a, Joyce-a, Picasso-a, pa su nam već i oni pomalo staromodni. Revolucija igra tango iz Burskog rata, mi držimo da je Rock prespor ...

Kao Théophile Gautier na premijeri Hugo-Verdi-jevih „Hernani“-a, građanska klasa oblači crveni prsluk da sablazni revoluciju, koja po istorijskim foajeima već uveliko hoda u salonroku sa kamelijom u zapučku ...

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Na Rosandićevoj izložbi

Publikovano u Odabrana dela Borislava Pekića, knjiga 12, Tamo gde loze plaču, (str. 402). - Beograd, Partizanska knjiga, 1984, © Borislav Pekić.

Senzualna nežnost. Iskustva Lezbosa u drvetu. Majke koje ostaju i kad svega nestane. Jedan Hristos koji liči na mučenika našeh veka. Ticijanovi anđeli ...

Rosandić daje svojim oblicima sekundarno patološki pečat. Klasika je tu pokvarena iznutra.

(A on objavljuje Strašni Sud – Modernoj!)

Ipak, vrlo dubok utisak ...